This essay was adapted from a recent lecture, formerly entitled The Listening of Art, given at Night School on April 17, 2024.

I’ve been dwelling on the concept of attention of late. If you’re reading this, I appreciate you lending your highly coveted attention to this essay. In our everyday language, you can pay attention, attract or grab attention. It’s something you can hold, though shortening attention spans suggest otherwise, and yet corporations can bid for your attention in the multi-billion dollar “attention economy”. So, what is “attention” exactly?

The word derives from the Latin attendere, meaning “to stretch toward.” It’s an image I find deeply moving: that something could so captivate us that we are compelled, physically and mentally, toward it. The word attencioun first appears in Middle English in the late 14th century, meaning “the active direction of the mind upon some object or topic”, conveying a relationship between the observer and observed. By the middle of the 18th century, the word evolves to mean “consideration, observant care”, emphasising the nature of this relationship as one of devotion — even stewardship — between the observer and the observed. This romantic way of experiencing the world undergoes a jarring transformation just over a century later in the late 19th century. “Attention” is defined as “the power of mental concentration”. No longer a relational act, attention turned inward, away from the world, toward the isolated ego.

CORRUPTED ATTENTION

I simultaneously feel a sense of mourning and identification with this linguistic shift. What a joy it might be to exist in a state of blissful intrigue; to be beckoned closer by other people, places and things? Yet, here we are doom scrolling alone, chasing gratification at the end of a timeline we’ll never reach.

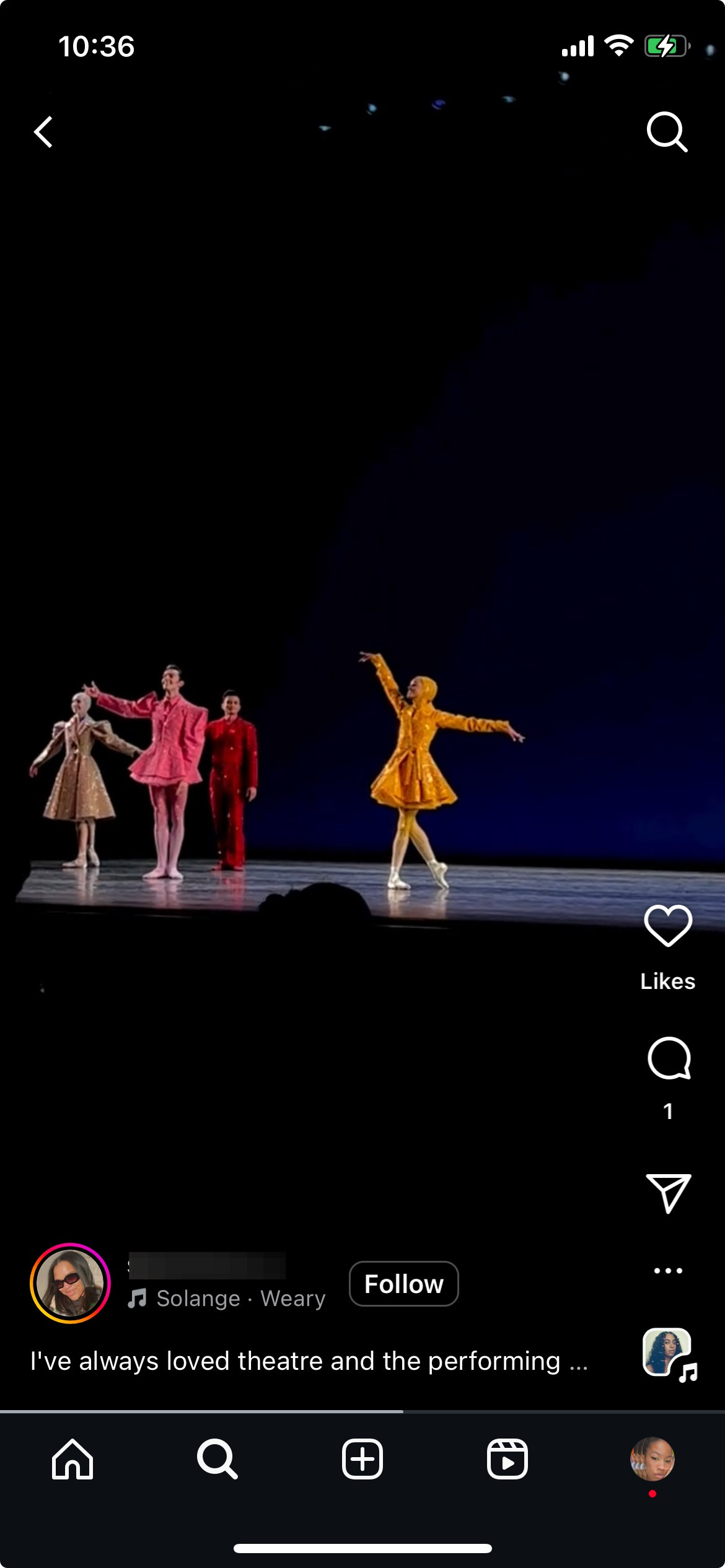

This dissonance between the romantic potential of attention and its current fractured form struck me with particular clarity in a real-world encounter with art. I remember attending the New York City Ballet in 2022 for a triple bill featuring a piece scored by Solange Knowles. The piece became colloquially known as “The Solange Piece” even though it was choreographed by a young choreographer named Gianna Reisen. While waiting outside the auditorium — having arrived late for the first act—I saw people leave the auditorium mid-performance to take photos of themselves in the empty balconies of the Lincoln Center while “Solange’s piece” wasn’t on. When the hotly anticipated performance finally arrived, phones lit up and angled toward the stage to capture scenes of the Swarovski-encrusted costumes already diffused across thousands of Instagram posts from previous nights.

What struck me was the realisation that there was a greater interest in telling the story about oneself “seeing” the art than actually experiencing the art itself. Where attention might have built bridges between artist and audience, it now builds pedestals for our egos.

Like Narcissus, we’re fatally absorbed with our own image. And our cultural institutions only reinforce a mode of looking that privileges performance over presence.

Take “The Art World” for instance. As a profit-seeking institution, it doesn’t care for creating proximity or connection. In fact, it seeks to manufacture the opposite: distance. Through spatial, linguistic and social architecture we are alienated not only from the art but the people around us. Overly intellectualised language mystifies the work making it feel unintelligible to the everyday admirer, while pristinely minimalist— or conversely palatial — spaces render the art too precious to approach, lest we contaminate it with our commonness. Carefully curated crowds of cool kids and industry insiders inspire a craving for acceptance that is never truly granted. It is in this distance that aspiration is conjured—aspiration that can be conveniently packaged, bought, and sold.

Though most of us can’t afford the membership fee, we can at least fashion the illusion of adjacency. Open Instagram, post a photo of the night— curated with just the right degree of indifference — tag the gallery and the artist, and await the parasocial affirmation that your attendance meant something. Meanwhile the gallery’s social intern adds another engagement data point to the stakeholder deck. You gained clout, but what about connection?

This isn’t an indictment of your gallery selfies. It’s an invitation to consider a richer, more connected way of engaging — one anchored in presence rather than performance.

RECLAIMING CONNECTIVE ATTENTION

We can re-appropriate the very architectures used to establish distance and instead use them to generate proximity: to the art, to the artist, and, most importantly, to each other. After all, art has always been a social practice, from ancient cave paintings to folk dances to rap.

As writer and psychoanalyst Anouchka Grose writes in Uneasy Listening, “Seeing and being seen, speaking and listening are fundamental to our social existence. They are how we learn to understand (and, perhaps more importantly, misunderstand) ourselves in relation to others.”

To find and express ourselves more richly requires not just expression, but also a practice of listening. Perhaps listening itself can be a kind of provocation and instigation, to find ourselves within each other.

LEARNING TO LISTEN AGAIN

The theatre is a very immediate arena for the social practice of listening. A group of strangers sit together peacefully in a space and collectively agree to listen, allowing another group of strangers to tell a story wholly and without interruption. As the lights dim, you shut out the noise and the notifications. The self recedes for a while. In this moment, you are not the main character. As an audience, we open ourselves to the provocation to feel and to be moved; instigating a conversation that will ripple and resonate far beyond the final curtain.

This kind of collective, receptive attention isn’t necessarily innate — it’s learned. We’re taught to read, write, and speak — skills that serve outward expression. But rarely are we taught how to listen, how to receive with care. If we are to reclaim attention as a connective act, we must re-learn how to receive others’ stories. Listening — not merely hearing — is the first act of relational attention. I wish to offer a few meditations that might guide us toward this practice:

No expectation, more sensation. If you anticipate, you’re not really listening.

Our expectations can suffocate the work and our own curiosity, both of which ultimately lead to the deficit between expectation and reality that we know as disappointment. To truly listen, we must shed pre-conceived notions of what the work might be and receive the work as it is. After all, some of the most compelling stories are born from the unexpected.

Imma let you finish. Listen fully before you try to make sense of it.

Where the internet has conditioned us to transfer meaning quickly, clearly and unequivocally, we have sacrificed the ability to accept unknowability; to sit in the limbo with the artist as they attempt to make sense of themselves. Art and content are not the same. Where content is fast and snackable, art requires a certain empathy and patience to be received. The best we can offer is the observant, caring type of attention.

Let it be messy. You don’t need to “get it” immediately (or ever…)

Unlike machines, humans are non-binary, inconclusive and messy beings. Listening and expressing oneself artfully shouldn’t be an exercise in clarity, but an embrace of honesty and nuance. Neat categorisation robs us of the richness of the human experience. Learning to sit in and accept the various shades of grey, offers us license to exist and tell our stories more truthfully.

Let’s unpack that? Art lives in conversation.

Expression isn’t a mandate, but a provocation for us to consider and respond to as witnesses. I’m less interested in word for word accounts, or static images of what took place, and far more concerned with what we do with the work as witnesses. How were you moved? What did it provoke within you? In conversation, we keep the work alive and invite others in.

Live it, then let it go. Record in your body, not on your phone.

While it's tempting to try and grasp onto the ephemeral, our screens become the middleman between us and the encounter. We fuss over the exposure and framing of the photo, rather than absorbing all the sensations of the experience. The phone eats first, leaving the body famished of sensation and connection. A photo may be worth a thousand words, but the body holds a lifetime of stories.

Susan Sontag, said it best,

May these meditations help us seek the right kind of attention; one that privileges presence over visibility, resonance over relevance. May our attentions stretch beyond ourselves and towards one another.

May we listen carefully.

Love this